This article explores how Western companies, from colonial trading firms to global corporations, cracked the Eastern market first through force and empire and later through strategy, adaptation, and globalization. Over the centuries the methods changed, but the underlying goal remained the same: to expand influence, capture markets, and shape global trade. Let’s see how the Western playbook not only entered the East but also built a system that positioned the West at the center of the global economy.

Before the 1500s, the East was far ahead of the West in science, trade, culture, and innovation. China gave the world paper, printing, gunpowder, and the compass, and dominated global trade through the Silk Road. India pioneered mathematics with the concept of zero and the decimal system, advanced in metallurgy and Ayurveda medicine, and thrived as the world’s leading source of textiles and spices. The Middle East advanced astronomy, medicine, and mathematics, preserving Greek knowledge and creating algebra. Meanwhile, Europe struggled through the Dark Ages, making the East the true center of knowledge, culture, and wealth during this period.

From the 1500s onward, the balance began to shift. Europe’s Renaissance and the Age of Exploration fueled rapid progress in science, navigation, and weaponry. Western powers such as Spain, Portugal, Britain, and the Netherlands opened new trade routes, built colonies, and extracted immense wealth from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. While America was laying the foundations of modern education and business, with institutions like Harvard University founded in 1636, India saw the rise of the Maratha Empire, led by great warriors such as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj (born 1630),who challenged Mughal dominance and strengthened regional power. By the late 1700s, the United States had gained independence, and Europe was entering the Industrial Revolution, where science and manufacturing would transform it into the world’s leading power.

The 19th and early 20th centuries marked the peak of Western dominance. The British Empire ruled nearly one-quarter of the world’s land and population, with colonies like India, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia), and Hong Kong supplying vital resources like textiles, rice, rubber, and tea. Across the Atlantic, the United States emerged as an industrial powerhouse, leading in steel, oil, and manufacturing, while corporations such as Ford, General Electric, and Coca-Cola extended its global influence. Britain expanded through colonies and direct rule, and the U.S. advanced through trade, technology, and business networks, together cementing Western supremacy in the East.

The two World Wars further reshaped the global balance of power. World War I (1914–1918) weakened many European empires, including Britain, even as it still held vast colonies in the East. World War II (1939–1945) accelerated this decline, draining resources and pushing Asian nations toward independence. In contrast, the United States emerged stronger from both conflicts, with unmatched industrial capacity, financial strength, and growing global influence. By the mid-20th century, America had replaced Europe as leader of the Western world.

After 1945, the U.S. dollar became the world’s trade currency, giving the West enormous financial leverage. Decolonization swept across Asia, but the West still held influence through corporations, banking, and the dollar system. By the late 20th century, globalization and China’s opening to trade pulled Western companies even deeper into the East. Even today, while China and others push alternatives, the dollar remains the backbone of world trade, a hidden tool that helped Western companies crack the Eastern market.

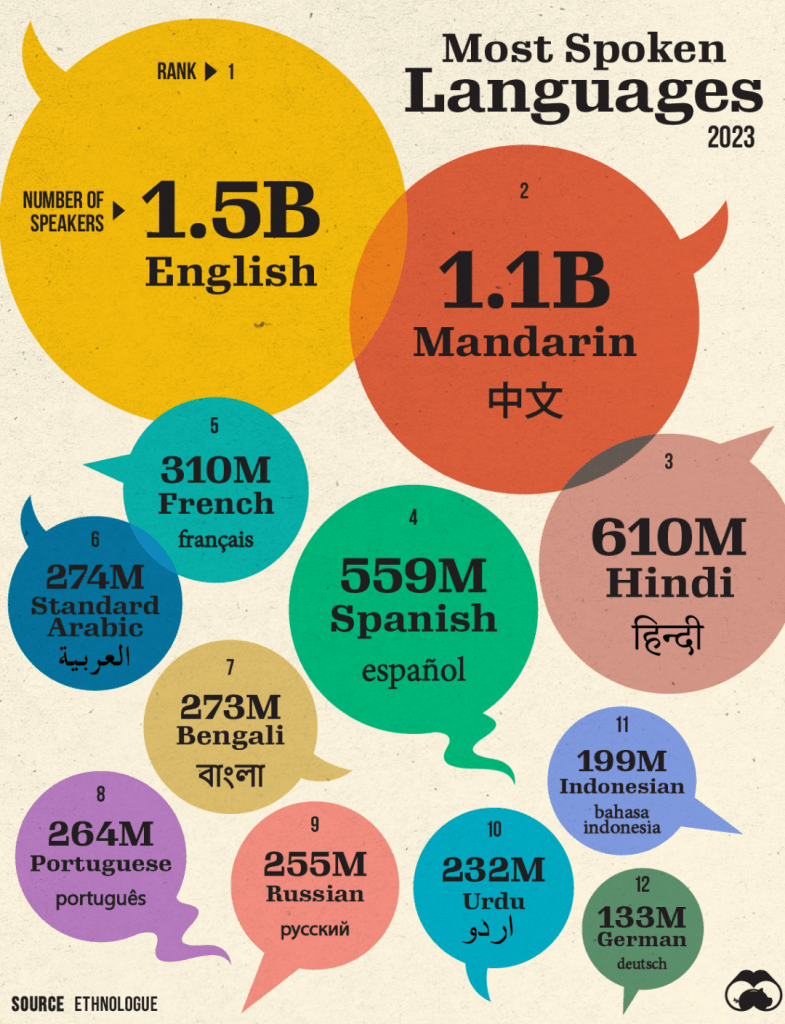

Language Dominance: The Silent Weapon

After colonizing, the West did not just leave; it left behind its language, education system, and lifestyle, which continued to shape the East long after political control ended. English became the backbone of administration and education in countries like India, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines, creating a common ground for trade, governance, and business. Prestigious universities such as Harvard, Oxford, MIT, and Cambridge trained generations of Eastern leaders, sending them back with Western frameworks of business and ambition. More than armies or empires, it was language that became the West’s strongest weapon, giving its companies a decisive edge in contracts, negotiations, and global trade.

The Western education system created a steady pipeline of talent from the East into Western corporations. By adopting Western-style schooling at home and sending students abroad for higher studies, Eastern societies produced graduates already trained in Western methods of management, law, and science. Western companies could then hire this talent with ease, using their skills to expand global operations, manage cross-border trade, and develop new technologies. In effect, the very systems once introduced to administer colonies ended up supplying the workforce that powered Western corporate expansion.

Today, English is the most spoken language in the world, with over 1.5 billion people using it as the common language for business, diplomacy, science, and technology. It is the default medium of global communication, from corporate boardrooms to academic journals and digital platforms. Strengthened by Western media and culture, English continues to symbolize modernity and opportunity. This linguistic advantage penetrated deep roots into the East, influencing mindsets and turning future generations into both consumers and workforce for Western companies.

Investment: The New Form of Control

As most of the East comprised of developing countries with limited industrial capacity and struggling finances, direct investment from the West became both a necessity and a lever of influence. Western corporations and banks funded infrastructure, factories, and supply chains, positioning themselves not just as business partners but as essential drivers of modernization. Companies like Ford and General Motors set up automobile plants in India and China, Unilever built extensive consumer goods networks across Asia and Africa, and Nestlé established factories that embedded its products into everyday diets. In telecommunications and energy, Western firms financed projects that locked local economies to Western technology and standards. This flow of capital created a one-sided dependency: while the East gained industry and jobs, Western companies secured privileged access to resources, labor, and consumers.

Cultural Influence: Selling Aspirations and Ruling the Colonial Mindset

Beyond finance, education, and investment, the West extended its reach into culture and consumer aspirations. Hollywood movies, pop music, and global advertising shaped ideals of modern living, turning Western brands into symbols of success and progress. Levi’s, Pepsi, and Pizza Hut became everyday markers of a modern lifestyle, while Nike, Apple, and Starbucks rose as aspirational icons for the middle class across Asia and Africa. For millions in the East, buying a Western product was not just a purchase but a statement of status and identity.

The strength of the U.S. dollar amplified this influence. Advertising that was costly in local currencies became cheap when paid in dollars, allowing Western brands to dominate TV, billboards, and newspapers. In the East, where joint families often lived together and shared a single television, one Coca-Cola ad during a cricket match in India or a drama in China could reach entire households, spreading from urban cities. Local companies, constrained by weaker currencies and smaller budgets, could not match this scale. The result was not just market control but cultural dominance, as Western brands captured imagination and aspirations.

Affordability Strategies: Reaching the Roots

As developing countries had limited purchasing power, Western companies adapted by breaking products into smaller, more affordable units. Instead of selling full-sized shampoo bottles, firms like Unilever popularized single-use sachets that could be bought for a few cents, making branded goods accessible even in rural markets. Coca-Cola introduced smaller bottles, and Nestlé sold single-serve packets of instant coffee and milk powders, turning occasional luxuries into daily habits. These tactics not only boosted sales volumes but also allowed Western brands to penetrate deep into the mass market, rooting themselves in daily consumption routines.

But affordability alone was not enough. To win trust, firms adapted to local tastes. McDonald’s in India introduced vegetarian items like the McAloo Tikki burger and removed beef from its menu to align with cultural and religious practices. KFC in China expanded beyond fried chicken, adding rice dishes and regional flavors that resonated with local tastes. Pizza Hut in Asia customized its menu with seafood toppings and spicier sauces to appeal to regional palates. By reshaping their offerings to match consumer expectations, Western companies created products that felt both aspirational and culturally familiar, securing broad acceptance in diverse Eastern societies.

The Corporate Playbook: Strategy and Adaptation

Western companies cracked Eastern markets not by chance but through a deliberate playbook that worked across countries. They used financial muscle, smart pricing, cultural sensitivity, and strong partnerships to outspend competitors, win consumer trust, adapt to local expectations, and bypass regulatory barriers. Walmart entered India through Flipkart, Volkswagen and General Motors partnered with SAIC in China, BlackRock partnered with Jio to launch a joint venture in India’s fast-growing digital and financial ecosystem, and McDonald’s entered Japan through Den Fujita, positioning burgers as the taste of modern America. These strategies allowed Western firms to scale quickly, cement their hold on markets, and remain resilient across diverse economies.

East is Turning the Tables

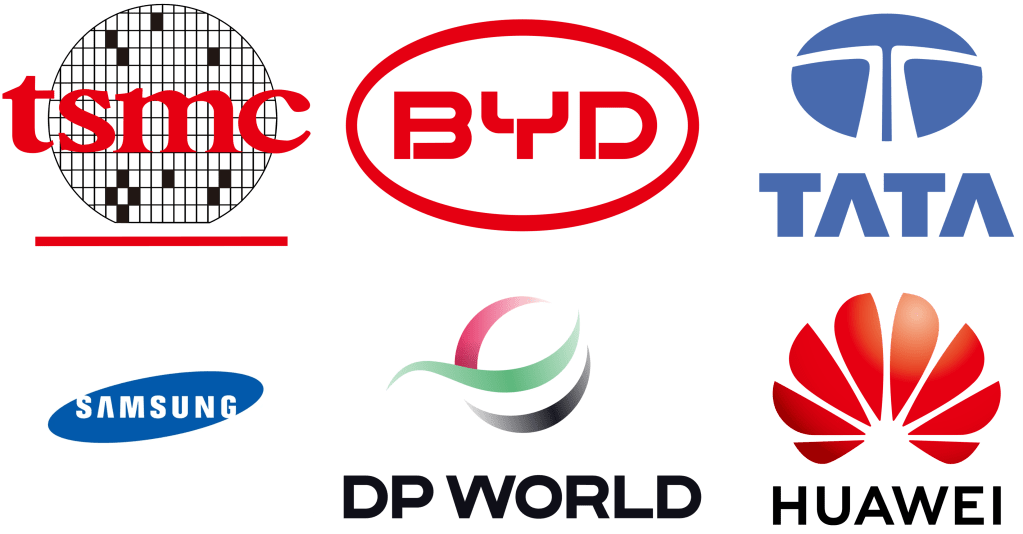

For centuries, Western companies relied on force, finance, language, culture, and strategy to crack the Eastern market. But today, the script is reversing. Eastern corporations are adopting the same playbook and pushing aggressively into Western markets. Huawei is challenging Western telecom, Samsung dominates electronics, BYD is disrupting autos with affordable EVs, and Tata has taken over Jaguar Land Rover. Japan’s Toyota leads global autos, Sony reshaped entertainment, and Taiwan’s TSMC produces most of the world’s advanced chips, making it the backbone of electronics and AI.

The Middle East, once seen only as an oil supplier, is also rewriting its role. DP World controls ports across continents, while Emirates Airlines has turned Dubai into a global hub for travel and trade. Together, India, Japan, Taiwan, and the Middle East show that the East is no longer just a market for Western dominance but a rising force shaping global trade, technology, and connectivity.

Conclusion

Unlike Asia and Africa, which had to fight for independence from colonial rule in the 19th and 20th centuries, Europe was the colonizer, and North America gained independence much earlier in the late 18th century. This early freedom gave the West a head start, politically stable, economically integrated, and already shaping global trade while much of the East remained under colonial control. That uninterrupted progress allowed the West to industrialize faster, build capital, and project power worldwide.

But every era has its turning point, and today the East stands at one. With its vast population, abundant resources, and growing technological edge, the East has the power to turn scale into global strength. Companies from Asia and the Middle East are no longer following Western footsteps; they are writing their own playbooks, investing abroad, shaping culture, and setting new standards. The future will not be defined by who dominated first, but by who adapts faster, innovates deeper, and leverages opportunities better. The stage is set for the East to rise, not as a follower, but as a leader in the next chapter of globalization. Power is shifting, markets are evolving, and the East is now beginning to set the rules of the game.

“The empires of the future are the empires of the mind”

– Winston Churchill