China, the world’s second-largest economy at nearly $20 trillion, has transformed itself in less than five decades from a developing nation into the world’s manufacturing hub.

Once known primarily for its vast population and low production costs, China today sits at the center of the world’s supply chains. The real question, however, is this: how did a country governed by a one-party system, and once economically comparable to nations like India, outpace nearly every competitor in manufacturing and trade? What strategic choices compounded China’s advantages into dominance over modern supply chains?

Human Capital: The First Engine of Industrial Power

Industrial strength begins with people.

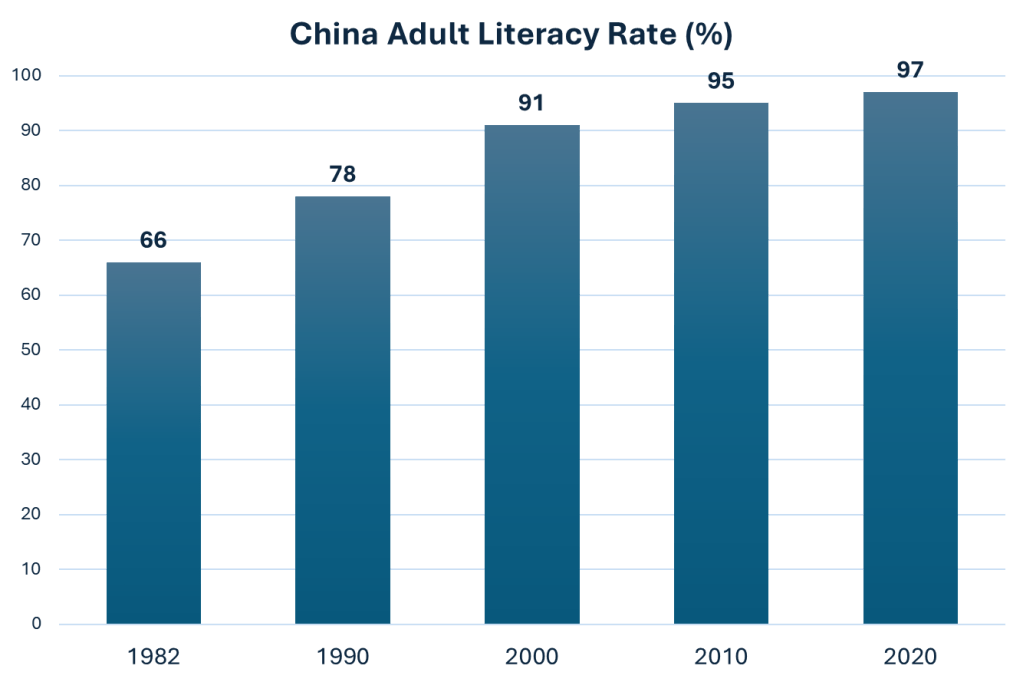

In 1982, China’s literacy rate stood at roughly 66 percent. By 2020, adult literacy exceeded 97 percent. This was not incidental progress, but policy-driven investment. A workforce capable of reading, learning, and executing complex processes allowed China to absorb industrial skills at unprecedented scale.

Education translated directly into productivity, and productivity into poverty reduction. Since the late 1970s, China has lifted over 800 million people out of extreme poverty, accounting for more than 70 percent of global poverty reduction during that period. In 2020, China officially declared the eradication of extreme poverty under the World Bank’s international poverty line.

A literate population does more than staff factories. It enables faster technology adoption, tighter process control, and the formation of dense manufacturing ecosystems that reinforce themselves.

What Actually Defines a Developed Country

Development is often measured through GDP per capita or income levels. But at its foundation, development is INFRASTRUCTURE.

Three elements form the foundation of infrastructure: water, electricity, and roads.

When these are reliable and widespread, everything else becomes possible. Factories can operate anywhere, not just in major cities. Housing follows industry. Employment follows housing. Consumption follows employment. Growth becomes decentralized, resilient, and self-reinforcing.

China understood this early. Infrastructure was not treated as a consequence of growth, but as its prerequisite.

Government Policy: The Architect of the Economy

For years, China was widely criticized for its centralized political system. Yet this same structure allowed the country to move faster than most democracies.

While democratic nations often face delays from elections, policy reversals, and prolonged debate, China’s one party system enabled long term planning and decisive execution.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping’s reforms opened China to global trade and foreign capital. Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Xiamen offered tax incentives, modern infrastructure, and regulatory clarity. These zones became controlled laboratories where industrial policy was tested, refined, and scaled nationwide.

At the same time, China invested heavily in highways, ports, power grids, and rail networks. Manufacturing was not merely encouraged. It was engineered.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

With foundational infrastructure in place, China became a low-risk, high-scale destination for FDI. Global firms do not follow incentives alone. They follow reliability.

China offered what manufacturers needed to operate at scale: an educated workforce, dependable power and logistics, favorable tax structures, and the ability to produce in massive volumes at competitive cost. Multinational firms could set up quickly, expand efficiently, and integrate China deeply into their global supply chains.

Companies such as Apple, Foxconn, Volkswagen, General Motors, Siemens, Intel, Bosch, Samsung, and Nike built large-scale manufacturing and sourcing operations across the country. China did not chase companies. It built the conditions that made them stay.

Reverse Engineering: Learning Before Leading

China did not attempt to innovate first. It chose to learn first.

Through foreign partnerships, joint ventures, and contract manufacturing, Chinese firms gained direct exposure to global production standards, machinery, and quality systems. Reverse engineering enabled manufacturers to internalize processes, reduce costs, and scale efficiently. This was not simple copying but systematic knowledge absorption.

Over time, imitation evolved into mastery. Companies such as Huawei, BYD, and DJI emerged as global leaders, compressing decades of industrial learning into a single generation.

Vertical and Horizontal Expansion

China’s industrial strategy expanded along two dimensions.

Vertically, firms integrated upstream and downstream, securing control over raw materials, components, assembly, and distribution. This reduced dependency, lowered costs, and improved reliability. A product assembled in Shenzhen could source components, packaging, and logistics within the same national ecosystem.

Horizontally, companies leveraged existing capabilities to enter adjacent industries. China moved from textiles and consumer electronics into automobiles, renewable energy, batteries, semiconductors and advanced manufacturing technologies.

The result was speed, resilience, and scale. China became a ‘one-stop’ industrial ecosystem where design, production, and logistics operate seamlessly.

Quality over Quantity

As China’s manufacturing base matured, the emphasis shifted from producing more to producing better.

Firms invested heavily in automation, process control, and quality management systems. Reliability and consistency became competitive advantages, not just low cost.

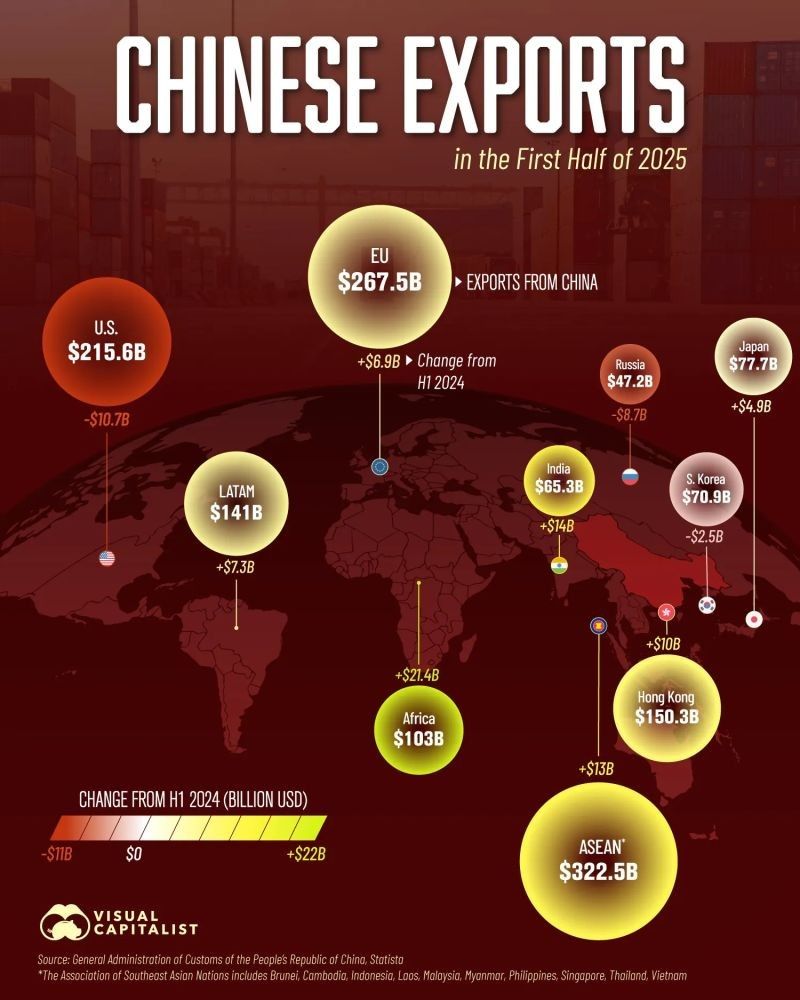

While many countries outsourced manufacturing in pursuit of short-term efficiency, China doubled down on capability. Supply chains concentrated where execution was strongest. Today, an estimated 150 of the world’s 195 countries depend on China for critical components, materials, or finished goods, reinforcing its central role in global manufacturing.

Control Over Critical Minerals

China’s influence extends beyond factories into the materials that power modern technology. It dominates the processing and refining of rare earth elements, lithium, graphite, cobalt, and manganese.

These materials are essential for semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, renewable energy, and defense systems. While many countries possess mineral reserves, few invested in the processing capacity to convert them into industrial inputs. China did.

This control over critical minerals deepens global dependence and provides strategic leverage across technology and energy supply chains.

Conclusion: The Power of Long-Term Thinking

China’s rise is one of the most important economic case studies of the modern era. Its demonstrates how long-term planning, policy continuity, and execution at scale can reshape an entire economy.

“Sometimes, in a democracy, the more time you give a large number of people to make a decision, the more likely the outcome is to be delayed and wrong.”

China’s centralized system allowed it to anticipate future demand and commit resources decades ahead. This is why the world now sees BYD alongside Tesla, Huawei alongside Apple, and SHEIN alongside Amazon. The same long-term thinking is visible in China’s early move toward automation, including dark factories, where production runs with minimal human intervention to maximize consistency, speed, and reliability.

The lesson is not about copying a political system. It is about clarity, commitment, and patience. Nations that align education, infrastructure, industry, and policy around the future do not just grow. They shape the world others must operate in.